Hey hey, and welcome back to lesson 3 of The Minimal Investor!

Lesson 2 Review – Diversification

We did a lot in lesson 2. Understanding market sectors, market classes, and fund types is a lot! Here’s a reminder of what we covered:

- There are a few different ways of slicing up investments

- Market Sectors – Technology, Health Service, Finance, Consumer Goods, etc

- Market Classes – US Market, International, Bonds

- Market Size – Large-Cap, Medium-Cap, Small-Cap

- Company Growth – Growth, Value

- Fund Types – Stocks, ETFs, Mutual Funds, Bonds

- Diversification means investing a portion in the US, international, and bond markets.

Lesson 3 Overview – Fees

We’re going to evaluate funds, then see which parts are the most important. For this lesson and all future lessons, we’ll be focusing entirely on ETFs and Mutual Funds.

I’m going to use the term ETF throughout this course, but these two are effectively the same. We won’t focus on individual stocks from here on out due to the fantastic diversification advantages of using ETFs that we talked about in lesson 2.

Here’s what we’ll be we’ll tackle in this lesson:

- What funds does your brokerage offer?

- What does all of this information about a fund mean?

- How do fees affect my portfolio long term?

- How do I choose between the rest?

At the end of this lesson, you should have a solid grasp on exactly which funds are best picks when evaluating them as a minimal investor.

1) What funds does your brokerage offer?

If you have a 401k, let’s start there. Log in to your brokerage account (Vanguard, Fidelity, etc.) and find the list of funds they offer. If you’re using a general stock trade company like E-trade, you’ll likely be able to invest in anything, but at a fee. If that’s the case, you can buy Vanguard ETFs from there. Head over and find your available funds list and come back.

If you check out the Vanguard list of funds, you’ll see there are 126 funds on this list. That’s a ton of funds! Let’s narrow this down a little. Make sure you’re viewing “Mutual Funds” and listing them by “Asset Class.” These classes should look familiar from lesson 2. Here’s a recap of all the asset classes that Vanguard offers:

- Money Market – This just means cash. These are comparable to a savings account.

- Bond – (Some Type) – Lending money in exchange for more money later. There’s a bunch of different bonds.

- Stock – If it just says “Stock” on Vanguard, that means US Stock Market.

- International – Anywhere outside of the US.

- Balanced – These funds combine multiple classes, including bonds, stocks, and international funds.

- Stock – Sector – These correspond to the market sectors from lesson 2 (Energy, Health Care, etc.).

After the last lesson, these should be familiar! We can even eliminate the “balanced” category since that one combines others.

We can also eliminate the “Money Market” category. Money market funds are for storing cash, not for investing in the market. Depending on your brokerage, when you make a deposit, it may start in a money market account. That’s OK for now – you can leave it there safe and then exchange it for funds later.

We can also eliminate “Stock – Sector” since that’s not as diversified as we’d like. That leaves 3 Asset Classes for us to focus on:

- Bonds

- Stocks

- International

Again, we’re back to the Simple Three-Fund Portfolio at Vanguard! These are the three groups that keep coming back. Let’s find one fund from each of these three asset classes.

Next Steps

- Find the list of funds at your brokerage

- See which assets class the funds in your brokerage are

2) What does all of this information about a fund mean?

When I first looked at a fund, I was overwhelmed by the amount of data available. When everything is important, nothing is important. What I didn’t realize is that only a few attributes of a fund are needed to understand it!

Let’s pick out some funds to analyze. In order to filter things out a bit more, let’s focus on only stocks for large companies. Filter the Vanguard Funds List for only funds that meet the following conditions:

- US Stock

- Large Cap only

This search will limit what’s shown to only US Stocks that include large-cap companies. It doesn’t mean these funds will only invest in large companies, but it does require at least 50% of the fund to invest in large companies. In fact, all of these invest at least 80% in the largest 500 companies.

We’ll take 3 funds from this list and compare them:

Side note: Do you see the FI Score on the left? That’s a Minafi-specific rating for which funds we believe to be the best for financial independence. After completing this course, I think you’ll agree with those ratings!

Looking at these three funds, it’s clear that they’re very similar. Vanguard allows comparing these funds, which help showcase the differences. Let’s take this row by row.

Symbol

The symbol of a stock is its unique identifier within a market used for buying, selling, getting prices, and all that. Whenever you refer to the fund, you’ll use the symbol. It’s also what you’ll use to buy and sell funds.

Asset Class

This is stock for all of these because they’re investing in companies. Later on, we’ll filter for international, but this comparison is about the US Stock Market.

Category

Again we already filtered for this, but large blend means the most companies in this fund will companies above ~$16 bln.

Risk Potential

This one is new! Risk potential is an indicator of the volatility of the fund. A risk level of 1 means the value will remain mostly the same (like cash). A score of 5 means you should expect extreme fluctuations in the price. Risk correlates directly with possible rewards. The longer timeline you have for investing, the more risk you can take on.

Expense Ratio

This is the most important number in the above chart! For Vanguard 500 and Total Market, this number is 0.04%, but for the Diversified Equity fund, this is 0.36% — that’s 9x higher! What does this even mean, and why the difference?

Side note: the expense ratio for $VDEQX is now 0.35%. It went down since that screenshot above

The expense ratio determines how much of your investment will keep the fund running. You don’t pay this fee directly, like with a financial advisor. Instead, the price of the fund will change depending on this fee. Here’s an example:

Let’s say you invested $10,000 in $VTSAX. Somehow, the price of the stock stayed even for the entire year (and didn’t give off any dividends – which we’ll talk about in lesson 8), you’d still have $10,000 in your account. If you invested $10,000 in $VDEQX and it stayed even then again, you’d have $10,000.

There’s a difference between these two. For the value of the fund to stay the same, the underlying assets would need to grow equal to their expense ratio. $VTSAX would need to rise 0.04% each year for your balance to stay the same. That increase wasn’t passed on to you, the stockholder. That increase is Vanguard uses to keep the fund in business.

For $VDEQX, the underlying assets needed to increase by 0.36% for you not to see a drop in your value!

Active Managed Funds vs Index Funds

The reason that $VDEQX has 9x the fees of $VTSAX is that it is an actively managed fund. Actively managed funds require human input to make the decisions on how to invest. Not every choice has a human behind it, but the strategy of the fund is controlled by a human whose goal it is to beat the market.

Index funds are tied to a specific market index and will invest in funds to match. For instance, the Vanguard 500 Index Fund tracks the 500 largest funds in the US stock market. Other funds, like the Vanguard Total Market fund, match an index that Vanguard defines specifically for this fund.

I only invest in index funds and wouldn’t consider investing in actively managed funds. Active funds seek to outperform the market, but research shows index investors make 3-4% more per year, pay fewer taxes, and experience less volatility. This is the approach Warren Buffet even advises new investors to pursue. I’d encourage you to only invest in index funds and not actively managed funds whenever possible.

Nav/Price

The last part of the chart is the Nav (Price) of the fund. To me, this a field you can ignore. The value of an individual share has no impact on anything useful. A higher price or a lower price doesn’t mean the fund is “better.” The last few days’ performances of a fund are no indication of how good it is.

It’s possible to buy a portion of a share, so there’s no need to worry about the price. If you have $16.42, you can invest just that much in a mutual fund.

Side note: Vanguard allows for partial investments – like the $16.42 example above – for mutual funds and ETFs. Some places only allow this for mutual funds and insist on buying whole shares of ETFs. This is one more reason I recommend (and use) mutual funds.

Past Performance

Looking at daily change, YTD change (year to date), one year, five years, ten years, and “since inception” number for a fund is not useful. Remember, from lesson 2 (diversification); funds are going to have up years and down years. It’s less critical to be in the fund that performs the highest and more important to be diversified.

Next Steps

- Look over the table of funds and filter them for large-cap blend index funds

- Find which funds are actively managed and exclude those.

- Look at fees charged for funds you have available.

3) How do fees affect my portfolio long term?

Fees are bad, but how bad are they? Let’s look at a scenario and see. Imagine you invested $10,000 in 4 different ways:

- Fund A: $10,000 in an index fund with a 0.04% expense ratio.

- Fund B: $10,000 in an actively managed fund with a 0.50% expense ratio.

- Fund C: $10,000 with an advisor who charges a 1% fee, who invests in a 0.04% index fund, effectively a 1.04% feed.

- Fund D: $10,000 with an advisor who charges a 1% fee, who invests in a 0.50% index fund, effectively a 1.50% feed.

Let’s assume all of these funds each gain 7% a year before fees. As we learned from (2), that means that the underlying assets of D will need to grow 8.5% (7%+1.5%), while fund A will only need to grow 7.04% (7% + 0.4%). Let’s see how much you would pay in fees over some number of years.

Fees Impact on Investment Growth

| Fund A | Fund B | Fund C | Fund D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fees | 0.04% | 0.50% | 1.04% | 1.50% |

| Invested | $10,000 | $10,000 | $10,000 | $10,000 |

| 10 yr value | $19,596 | $18,741 | $17,780 | $16,997 |

| 10 yr fees | -$76 | -$931 | -$1,892 | -$2,675 |

| 10 yr fees % | -0.40% | -4.70% | -9.60% | -13.60% |

| 20 yr value | $38,398 | $35,121 | $31,612 | $28,889 |

| 20 yr fees | -$299 | -$3,576 | -$7,085 | -$9,808 |

| 20 yr fees % | -0.08% | -9.2% | -18.30% | -25.30% |

| 30 yr value | $75,244 | $65,818 | $56,206 | $49,101 |

| 30 yr fees | -$879 | -$10,305 | -$19,917 | -$27,020 |

| 30 yr fees % | -1.20% | -13.50% | -26.20% | -35.50% |

The amount you pay in fees compounds over many years. After 30 years or so, you may have paid more in fees than your investment balance! It’s possible to invest $10,000 and pay $27,000 in fees over 30 years.

Even the difference between a fund with a fee of 0.04% and a fee of 0.50% is huge over 30 years – enough to justify choosing a cheaper fund for sure.

“But no one invests in those high fee funds, right?”

Right after college, my mom passed away. I inherited $100,000 from her and started trying to learn everything I could about investing to understand what to do with it. I talked to my bank, and they had financial advisors who could help those like me who didn’t know what to do.

The price for this help was a 1% investment advisor fee each year – regardless of how well the fund did. On top of that, some of the funds they invested me in had expense ratios above 1%! Some were even “load funds” – funds that charge a percentage fee when you buy into them (these are the absolute worst – avoid them like the plague).

The result was me paying upwards of 2.25% in fees. Over 30 years, this would mean 50% of my gains could go to fees. When I did the math on this, I was shocked! Did I really want to pay someone half my potential investment earnings so they could make a few decisions a year? Could I make those decisions instead?

Your Fees Visualized

If you’re already investing and want to understand how much you’re paying in fees now, you could create a spreadsheet and calculate this (the total amount invested * fee percent).

Or, if you’re looking for a tool to do it, you can use Personal Capital Retirement Fee Analyzer* and link it to your existing accounts. It will pull down a list of your investments, find out their fee %, and provide an overall fee % for your entire account. Here’s a snapshot of what mine looks like from Personal Capital.

Seeing this calculated for me is a gentle reminder of how I’m doing compared to other potential investments. I try to keep this as low as it can be while remaining diversified.

Takeaways

- Fees compound and can cost you a lot – maybe even half of your potential investment gains.

- Understanding fees allow you to rule out a bunch of overpriced funds.

4) How do I choose between the rest?

We’ve ruled out a bunch of funds for the following reasons:

- Funds are too specific (market sector)

- Funds are too broad (balanced / target retirement funds)

- Funds with fees that are too high

- Funds that are with an advisor who charges a fee

Even with these reasons ruling a bunch of funds out, there are still 9 funds to choose from for the US Stock Market category on Vanguard alone:

- 500 Index Admiral

- Dividend Appreciation Index Admiral

- Large Cap Index Admiral

- Total Stock Market Index Admiral

- Tax-Managed Capital Appreciation Admiral

We’ll skip the “tax-managed” one for now, but revisit it in lesson 8.

Side note: if you spot other finds that say “Investor” instead of “Admiral,” avoid those for now. This distinction determines what the minimum investment is for a fund. In 2019 Vanguard started eliminating “Investor” funds and lowering the cost of “Admiral” funds – allowing everyone to get the lower-cost funds with a lower minimum investment.

We’re down to 4 funds from Vanguards 126 – not too bad! The difference between these 4 won’t make a huge difference. You could invest in any of them and be in great shape.

The next refinement we can make to help choose The Fund is comparing assets under management. “Assets” is the total amount invested in that fund from all investors. The higher the assets, the more investors that are choosing that fund to invest.

Here are the key details for our funds:

| Fund | Expense Ratio | Assets |

|---|---|---|

| 500 Index | 0.04% | $341 billion |

| Dividend Appreciation Index | 0.08% | $30 billion |

| Large-Cap Index | 0.06% | $16 billion |

| Total Stock Market Index | 0.04% | $603 billion |

From this, we can see that the 500 Index and Total Stock Market Index funds have the lowest expense ratio. Total Stock Market Index has far more assets under management.

This doesn’t guarantee success, but it is a vote of confidence from our fellow investors. With that in mind, we can choose the Total Stock Market Index for our US Stock fund.

Adam Says: This doesn’t mean it’ll perform the best, or that it’s a sure thing – just that it’s a solid choice. The difference between these funds’ performance over a decade will be within a percent or two of each other. When in doubt, use the fund that more investors trust.

International Funds

If we did the same for International Funds, there would be a lot more funds to consider – and with harder to understand names. What we want to find is a single fund that invests everywhere outside of the US for a low fee. Because of that, we can rule out any funds that invest only in a specific area, have a high fee, or only invests in one particular type of international market (like real estate or developed markets only).

If you went through every Vanguard fund with these criteria, you’d find there are 2 funds that come up:

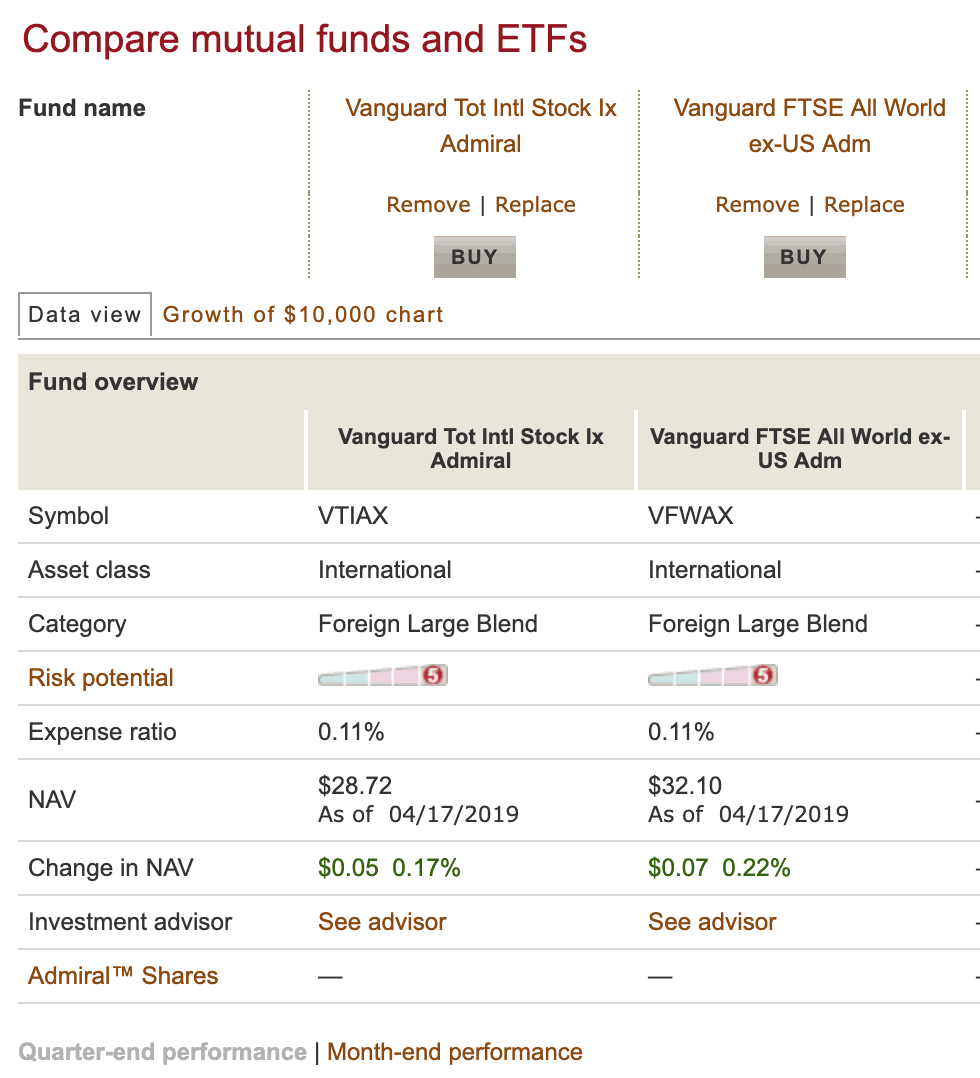

If we compare these two based on expense ratio, assets under management and how many companies the fund invests in.

| Fund | Expense Ratio | Assets | Fund Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total International Stock Index Admiral | 0.11% | $300 billion | 6,190 |

| Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US Index Fund Admiral | 0.11% | $33 billion | 2,600 |

I like to use Vanguards comparison tool for analyzing these:

The Total International Stock Index Admiral fund looks a lot like the US Stock we picked, but what’s that FTSE All-World ex-US one? These two look about the same. They even have almost identical performance over the last ten years. To break the tie, we can look at the number of companies they invest in and their assets under management.

With ten times the assets and over twice the number of funds, we can see that more people are choosing Total International Stock Index Admiral and that it’s also more diversified. That’s a good pick for an international fund.

Bond Funds

Bonds might be the most confusing of the three main categories to choose our best fund. When selecting a bond fund, you can use the same context as before – low expense ratio, a high number of bonds invested in within the fund, a high number of assets under the fund.

If you rule out any funds that are government only, are international funds, or target a specific period (short term, long term, etc.), only a single bond fund meets those requirements: Total Bond Market Index.

This fund invests in government and corporate bonds of varying periods – short term, long term, intermediate-term. It’s the only bond fund you need.

Takeaways

- Pick index funds with low fees and high diversification.

- Use the market cap of a fund as a tiebreaker.

- Look at the number of investments within the fund to understand how diversified it is.

Lesson 3 in Review

We went deep in this lesson to analyze funds and understand which ones we should choose. The rules for selecting funds are slightly different for US Stocks, International Stocks, and Bonds – but some concepts are the same for each. Investing in index funds that have low expense ratios is the key for all groups.

If you don’t invest at Vanguard, you can use the same principles to find the lowest cost funds at your brokerage. Find a single US Stock, International Stock, and Total Bond market fund wherever you’re investing today and add them to your spreadsheet – we’ll need them in the next lesson.

Side note: If you have a 401(k) you’ll have a limited selection of funds to choose from. If you’re investing with an account that you fully control outside your work, you may be able to use these same Vanguard funds.

Next Lesson

Before we make any investments, we have one more thing to figure out – which accounts to use. If we know we’re going to invest in the three funds listed here, how do you split the investments between a 401(k), IRA, Roth IRA,